The enactment of federal tax reform in December 2017 set off a scramble in the states, transforming what has often been a rote annual chore—updating tax conformity statutes—into a serious policy question with implications for state revenue, personal and business tax burdens, and the contours of state tax codes. More than a year out, some of the dust has settled and many states have made their choices. Nevertheless, much remains to be done. Some states have delayed a decision or have yet to grapple with the implications of inaction. State conformity to the new law’s international tax provisions remains particularly murky.

This paper updates and builds upon our tax conformity primer from January 2018, identifying which actions states have taken in response to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, delineating the ways that states do—and do not—conform, and highlighting issues likely to dominate the conformity debate in the coming year.

Each state has its own approach to taxation—its own combination of tax types, rates and structures, and rules and exemptions. These variations reflect a multiplicity of purposes and an array of fiscal aims, some with contemporary urgency and others lost to the ages. Yet even the most iconoclastic state tax structures draw upon the federal tax code, and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) has ramifications for those tax structures to which, even more than a year out, states have not fully adapted.

Some states adopt large swaths of the federal tax code by reference; others use it as a starting point, then tinker endlessly; and still others incorporate federal provisions and definitions more sparingly. In some states, the federal tax code is mirrored; in others, echoed. The differences matter greatly, but so do the points of agreement.

States conform to provisions of the federal tax code for a variety of reasons, largely to reduce the compliance burden of state taxation. Doing so allows state administrators and taxpayers alike to rely on federal statutes, rulings, and interpretations, which are generally more detailed and extensive than what any individual state could produce.[1] It provides consistency of definitions for those filing in multiple states and reduces duplication of effort in filing federal and state taxes. It permits substantial reliance on federal audits and enforcement, along with federal taxpayer data. It helps to curtail tax arbitrage and reduce double taxation Double taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. . For the filer, it can make things easier by allowing the filer to copy lines directly from their federal tax forms. In the words of one scholar, federal conformity represents a case of “delegating up,” allowing states to conserve legislative, administrative, and judicial resources while reducing taxpayer compliance burdens.[2]

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Delegating up, of course, means ceding a certain amount of control, hence the myriad of ways that states modify or decouple from the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). Most pertinent, perhaps, is that federal tax changes have implications for state revenue.

Absent some sort of policy response, most states stood to see increased revenue due to federal tax reform, with expansions of the tax base reflected in state tax systems while corresponding rate reductions fail to flow down. The extent to which this is true (and indeed in some cases, whether it is true) depends on the federal tax provisions to which a state conforms. In the first legislative year following the late 2017 federal tax reform, legislators in many states took steps to shield individual taxpayers from an unlegislated tax increase, but frequently showed less solicitude toward business (and especially corporate) payers. For instance, in contrast to the swift action many states undertook with individual income taxes, the response to the potential unlegislated taxation of international income has been lumbering at best.

Where states have postponed their conformity debate, or neglected to adopt offsets to the new revenue, there remain important opportunities in 2019. In many cases, states would do well to balance their reforms to the individual income tax with revisions to the corporate tax structure, particularly in conforming to the new law’s improved treatment of capital investment. And where states are poised to expand their tax base The tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. beyond the water’s edge, there is still time to address this significant unintended consequence. In the wake of federal tax reform, states have a golden opportunity to move their own tax codes in a more simple, neutral, and pro-growth direction.

All states incorporate parts of the federal tax code into their own system of taxation, but how they do so varies widely. In broad terms, however, approaches to IRC conformity can be divided into three classes: rolling, static, and selective.[3]

States with rolling conformity automatically implement federal tax changes as they are enacted, unless the state specifically decouples from a provision. This autopilot approach tends to provide the greatest clarity and predictability for taxpayers, though at a modest cost of state control.

Static (or “fixed date”) conformity also incorporates wholesale updates of the federal tax code, but to the IRC as it existed at a specific point in time, rather than adopting all changes on a rolling basis. Some such states conform legislatively every year and are functionally identical to states with rolling conformity, albeit with a measure of added uncertainty. Others are inconsistent and may even conform to an outdated version of the IRC for many years.

Finally, a handful of states only conform selectively, incorporating certain federal provisions or definitions by reference, but omitting large swaths of the federal tax code and forgoing the use of federal definitions of income as their own starting points for calculation.

No state, of course, conforms to every provision of the Internal Revenue Code. Each state offers its own set of modifications, additions, and subtractions to the code. Each adopts its own set of rules and definitions, frequently layered atop those flowing through from the federal code. But from definitions of income to exemptions to net operating losses, and even what filing statuses are available and whether a taxpayer can itemize their deductions, the federal tax code consistently informs state-level taxation.

In the course of about two hundred pages, the 2017 tax reform bill fundamentally remade significant aspects of the tax code and substantively modified many others.[4] Only some of these changes, however, had the potential to alter state tax systems. Among those with state impacts are:

In aggregate, the base-broadening provisions are worth considerably more than the base-narrowing ones. Each provision changed at the federal level has varying impacts on states, though, and each will be considered in turn.[5] In the tables that follow, provisions where conformity is expected to increase state revenue are indicated with a (+) and those where conformity may result in a loss of revenue are denoted with a (-). To the extent that states punted on conformity in 2018 or received additional revenues without determining how to use it, opportunities for tax reform may present themselves. Because many states have yet to issue guidance on international provisions, moreover, a great deal of uncertainty remains, including how much revenue is at stake. As state legislators grapple with what these provisions mean for their state, it is vital that state fiscal offices provide estimates of the effects of each relevant provision.

State and local individual income taxes account for 23.5 percent of state and local government tax collections nationwide, compared to the 3.4 percent which comes from corporate income taxes.[6] Consequently, even though the 2017 federal tax reform bill made more changes to corporate than personal taxation, the latter are of far greater significance to state government finances (especially for states which disclaim any new international income). This reality showed up in state conformity responses in 2018, with a far more robust response to individual income tax changes than to corporate base broadening. Thus, corporate (and particularly) international base broadening Base broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. loom large in more states in 2019, though in states that have yet to address the individual income tax base-broadening provisions, the more significant revenue implications are associated with individual income taxes.

At the federal level, individuals now receive the benefit of a higher standard deduction, rate cuts (along with broader bracket widths), a more generous child tax credit A tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. , and a higher alternative minimum tax (AMT) exemption threshold. To help pay for these changes, the personal exemption has been repealed, the state and local tax deduction is capped at $10,000, the mortgage interest deduction now applies to the first $750,000 of principal value (down from $1 million) and was eliminated for home equity indebtedness in its entirety, and several deductions were eliminated outright. The vast majority of filers received a tax cut at the federal level,[7] but because base-broadening measures flow through to many states, while rate reductions do not, many faced a state tax increase in the absence of legislative action to prevent one.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

An increase in the standard deduction and the repeal of the personal exemption were easily the most consequential changes for many states, and eliminating the personal exemption broadens the tax base considerably more than raising the standard deduction narrows it. The other changes, although not insubstantial, do not change the fact that for most states, the tax base is broader after federal tax reform, forcing states to decide whether to keep the additional revenue to grow government, cut rates to avoid an automatic tax increase, or use the broader base to help pay down broader tax reform.

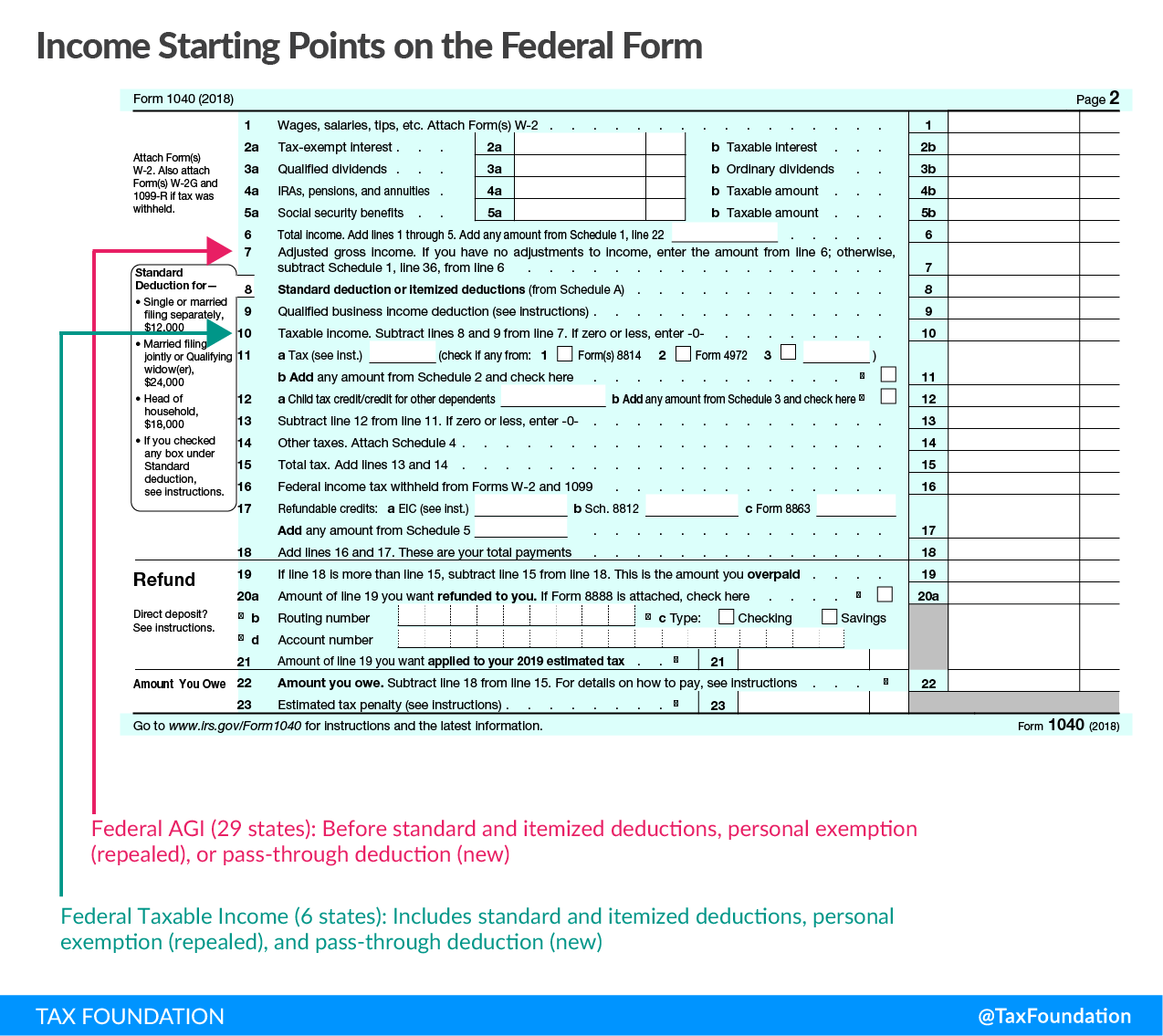

Although each has its own additions and subtractions, twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia use federal adjusted gross income For individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” (AGI) as their starting point for calculating individual income tax liability, including Vermont, which adopted federal AGI as its starting point beginning with tax year 2018. Another six states (Colorado, Idaho, Minnesota, North Dakota, Oregon, and South Carolina) use federal taxable income Taxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. .[8] The remaining six states which tax wage income[9] use state-specific definitions of income, although they incorporate some IRC provisions into these definitions.

Figure 1 illustrates how this concept plays out from the perspective of taxpayers on their individual income tax returns. In states which conform to federal AGI, taxpayers carry line 7 of the new federal return to their state return. In states which use federal taxable income, taxpayers start by copying line 10, which, as Figure 1 illustrates, includes additional deductions and exemptions, and thus carries with it more provisions from the federal system.

Electing federal taxable income as a starting point for state income taxes has the effect of incorporating federal standard and itemized deductions and a new deduction for qualified pass-through business income, unless the state expressly decouples from these provisions. Since the federal personal exemption, now set at $0, is also an element of federal taxable income but not federal adjusted gross income, states which begin with federal taxable income incorporate the elimination of the personal exemption unless they expressly decouple from the provision, while for other states, the implications of federal repeal vary depending on how state statutes are written. Each of these elements will be considered separately.

Figure 1.

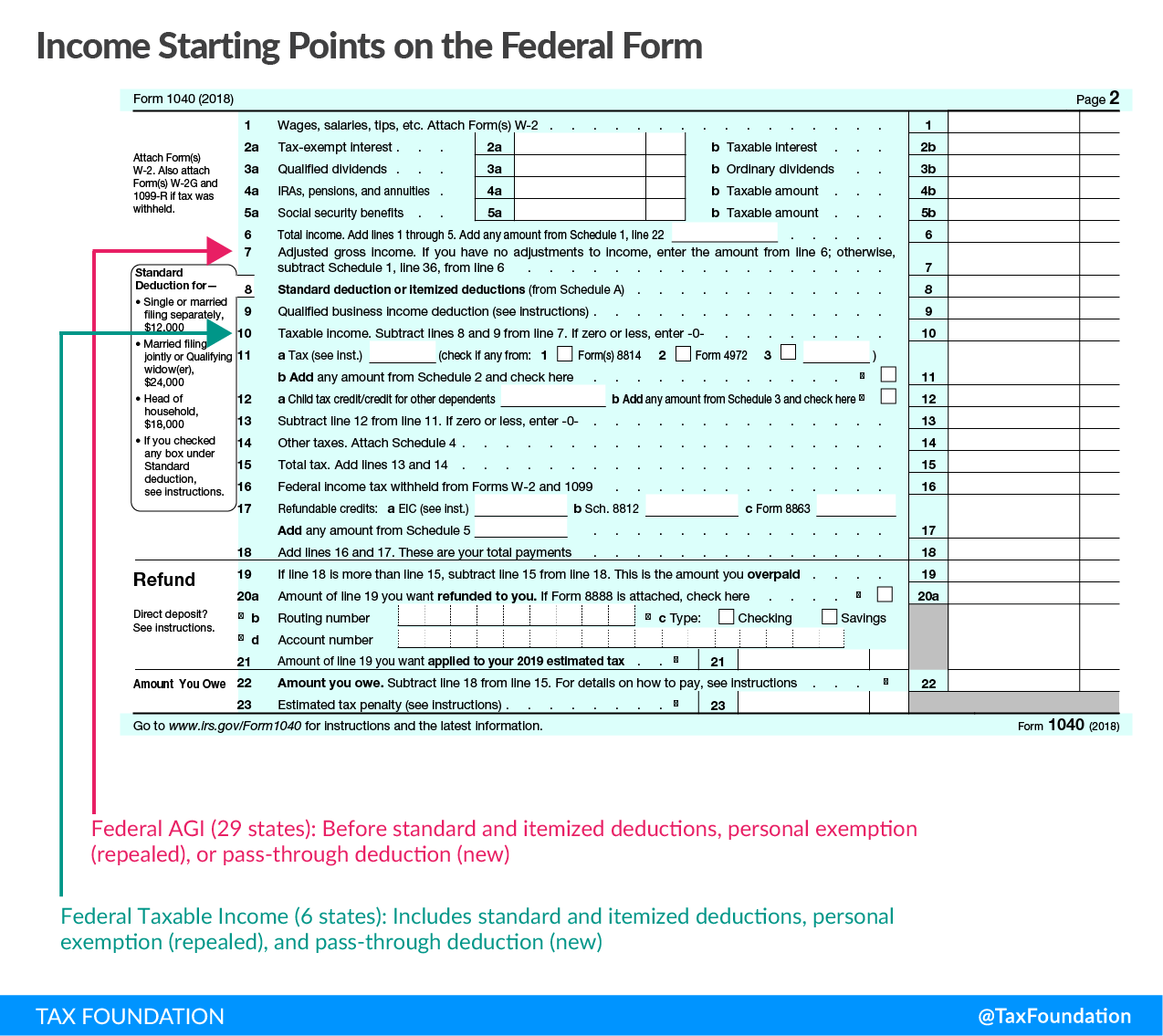

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have rolling conformity, nineteen have static conformity, and four only conform selectively without universal reference to a specific version of the IRC. Two states with their own state-defined income starting points nevertheless conform to the IRC: Alabama on a rolling basis and Massachusetts to a fixed year. Most, but not all, static conformity states adopt conforming legislation every year as a matter of course, albeit sometimes retroactively. Because the TCJA turned what had been a rote action for most states into a consideration with meaningful policy implications, the debate around conformity was more robust in 2018 than it had been in previous years.

Massachusetts conforms to the federal tax code as it existed in 2005, and California to the code as of 2015. They were behind on conformity before the enactment of federal tax reform, and remain so now. Heading into 2018, three other states—Iowa, Kentucky, and Oregon—had also missed one or more conformity updates. All three, however, brought their codes up-to-date in 2018, with Iowa and Kentucky doing so as part of broader tax reform efforts. Maryland enacted legislation temporarily decoupling from any new IRC provisions which have an estimated state revenue effect in excess of $5 million, but only administratively decoupled for one tax year and now conforms to provisions of the new federal law unless otherwise dictated by statute.[11]

At the same time, however, Arizona and Minnesota declined to act on conformity legislation, and thus continue to operate under the Internal Revenue Code as it existed prior to tax reform, while Virginia technically updated its conformity date but expressly decouples from all new provisions of the TCJA in effect 2018 and onward. These five states—Arizona, California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Virginia—are now the marked outliers on individual income tax conformity.

Figure 2 shows how states conform to the federal tax code.

Figure 2.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Even when static conformity states routinely incorporate updated versions of the federal tax code, the process introduces some measure of uncertainty, and the recent tax overhaul delayed decisions late into 2018 in some states. It is generally in a state’s best interest to conform to the current version of the IRC, though the revenue-positive nature of conformity under the new tax law motivated some states to cut rates or make other commensurate adjustments; other states which conformed without such adjustments may wish to consider them in 2019.

(a) Virginia has decoupled from most of the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the 2018 Bipartisan Budget.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

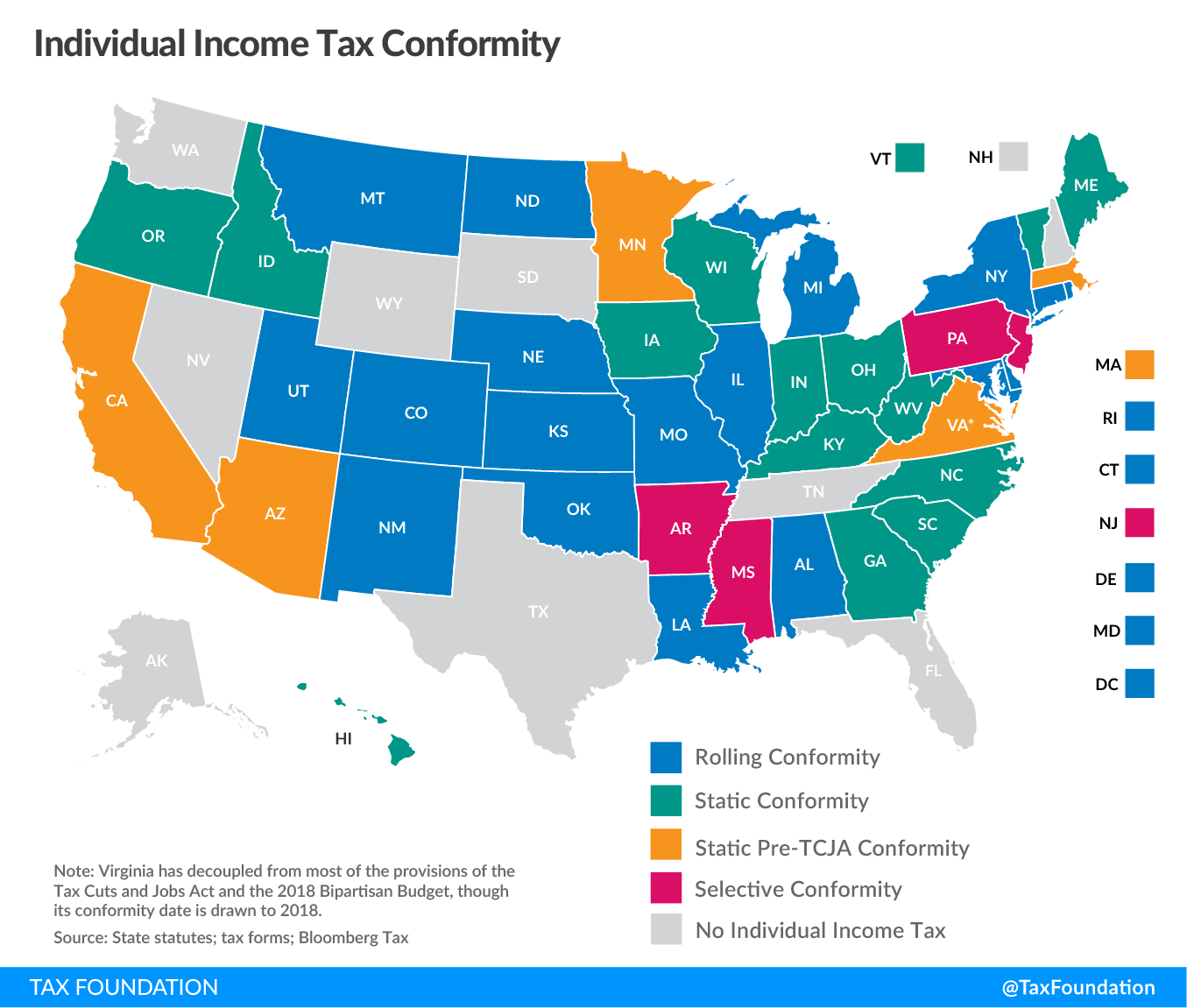

The new federal law dramatically increases the standard deduction, set at $12,200 per single filer (double for joint filers) in 2019, while repealing the personal exemption ($4,050 per person in 2018). These provisions resulted in the most profound revenue changes in many states.

On federal income tax forms, standard and itemized deductions, and the personal exemption, are below-the-line, meaning that they are claimed after arriving at one’s adjusted gross income (line 7 on the new Form 1040 for Tax Year 2018; see Figure 1), but before arriving at one’s federal taxable income (line 10). Therefore, if a state uses federal taxable income as the starting point for its income tax calculations, then it begins by incorporating filers’ standard (or itemized) deductions and personal exemptions as claimed at the federal level. If a state instead uses federal adjusted gross income as its starting point, then it begins its calculation without the inclusion of these deductions or exemptions.

It is, however, possible for a state which begins with adjusted gross income to expressly incorporate the federal standard deduction, personal exemption, or both, just as it is possible for a state beginning with federal taxable income to disallow them by adding back the value of those adjustments to the filer’s state taxable income. Figure 3 shows how states incorporate the federal standard deduction and personal exemption into their own tax codes.

Eliminating the personal exemption broadens the tax base considerably more than raising the standard deduction narrows it. At the federal level, those changes are paired with a far larger child tax credit, but that provision only flows through to four states, and then only in part.

Figure 3.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Conformity to the standard deduction is straightforward: states either use the federal standard deduction (as of current law or tied to a prior year), provide their own separate standard deduction, or forgo one altogether. With the personal exemption, however, there is an added wrinkle: many states set their own values for the personal exemption but use federal definitions of eligibility. Depending on how those statutes are written, the functional suspension of the personal exemption under the TCJA may also eliminate state personal exemptions even when states do not fully conform to the federal provision. Generally, states which grant an exemption for each one allowable at the federal level will see no change, but those which focus on credits claimed, or credits allowable on income tax returns, would no longer offer the exemption absent a legislative response.

Six states (Colorado, Idaho, Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Utah) saw the elimination of their personal exemption due to the new federal law. Three of these states (Colorado, Idaho, and North Dakota) adopted the new standard deduction and eliminated the personal exemption by virtue of their use of federal taxable income (FTI) as an income starting point. The other FTI states retain their exemptions, either because they conform to a prior year’s IRC (Minnesota) or because they expressly decoupled from federal treatment of the personal exemption (Oregon and South Carolina). In Missouri, a somewhat ambiguous statute was clarified (to affirm the personal exemption’s elimination) as part of a broader package of tax reform facilitated, in part, by the new federal law.

(a) Missouri has a state-defined personal exemption linked to federal exemptions actually claimed and worth more than $0, while Utah offers a credit calculated using the number of credits claimed on federal tax returns.

(b) Nebraska’s standard deduction is the lesser of a state-defined value and the federal standard deduction, and in the aftermath of federal tax reform, the state-defined deduction is the lower of the two.

(c) New Hampshire and Tennessee only tax interest and dividend income.

Sources: state statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

Many states incorporate federal tax deductions into their own codes, some of which have been modified or even repealed under the new tax law. Changes to both above-the-line and itemized deductions can have an impact on state revenues.

Above-the-line deductions are those which reduce adjusted gross income. (These are the adjustments made prior to line 7 in Figure 1.) They can be claimed by all filers, regardless of whether they choose to itemize or take the standard deduction. At the federal level, examples of above-the-line deductions have included contributions to Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), interest on student loans, higher education expenses, health savings account contributions, moving expenses, and alimony payments, among other deductions.

Below-the-line deductions, by contrast, come after adjusted gross income. They have included the standard deduction and the personal exemption, considered previously, but also itemized deductions, which can only be claimed by filers who do not take the standard deduction. Common itemized deductions include those for state and local taxes, home mortgage interest, medical expenses, and charitable contributions.

The 2017 law repealed the above-the-line deduction for moving expenses (except for active duty military personnel), and temporarily lowered the eligibility threshold for taking the medical expense deduction for tax year 2018. The mortgage interest deduction, which formerly applied to the first $1 million in acquisition value, now applies to $750,000 in acquisition value, though existing mortgages are grandfathered in. Additionally, deductions for home equity indebtedness are no longer allowed.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Even a new $10,000 aggregate cap on state and local tax deductions affects states, even though it is commonly regarded (rightly) as a deduction against state tax liability. This is because many states allow a portion of the deduction (typically that associated with local property taxes) to be claimed, and limit the total size of the state deduction based upon the amount claimed on federal tax returns. In response to the new federal law, Hawaii and Iowa specifically decoupled from the $10,000 cap, while Maine now allows an addback for the share limited at the federal level.[12]

States which begin their calculations with federal taxable income incorporate itemized deductions by default, unless they specifically add back the value of a specific deduction. However, states which begin with adjusted gross income frequently offer these itemized deductions as well. If in doing so they tie them to the federal tax code rather than creating them as stand-alone provisions of their own codes, then the new federal changes will affect them as well.

Save for the medical expense deduction, which was available to a larger number of filers for tax year 2018, all these changes are base broadeners and will increase revenues for states which conform to these provisions. Where states have yet to update their conformity date, but would conform to these provisions upon doing so (absent specific legislation to the contrary), this is noted as “yes (prior year).”

(a) Computed based on how the provision existed in the IRC in a specified prior year, separate from the state’s general conformity date.

(b) New Hampshire and Tennessee tax interest and dividend income only.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

Federal tax reform doubled the size of the child tax credit, from $1,000 to $2,000, while dramatically increasing the refundable share, to $1,400. The credit is also available to a much wider range of taxpayers, since income phaseout thresholds rose dramatically.[13] At the federal level, the much larger child tax credit, along with a new $500 per-person family tax credit for dependents not eligible for the child tax credit, more than offsets the loss of the personal exemption for many filers.

Most states, however, do not offer such credits and thus did not conform to the provision, meaning that they gained (in many cases) from the repeal of the personal exemption without any obligation associated with the expanded child tax credit. However, four states—Colorado, New York, North Carolina, and Oklahoma[14]—offer child tax credits linked to a percentage of the federal credit (for instance, Colorado offers a credit in the amount of 30 percent of the value of the federal credit). The expanded credit represents an additional cost to these states. In 2018, Idaho adopted its own child tax credit, albeit a state-defined one, as part of a package intended to offset revenue increases from federal tax reform.[15]

Thirty-three states offer deductions for contributions to 529 education savings accounts, which may see increased use now that they can be utilized for primary and secondary, as well as higher, education. However, in some states the enabling legislation specifies use for higher education, which may result in a disallowance of state tax benefits to the extent that the accounts are used for primary and secondary education.

Notes: Table indicates whether state offers a deduction for contributions to 529 plans. Some of these plans may not be in compliance with the new federal law permitting withdrawals for K-12 educational spending. New Hampshire and Tennessee tax interest and dividend income only.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax; Tax Credits for Workers and Their Families

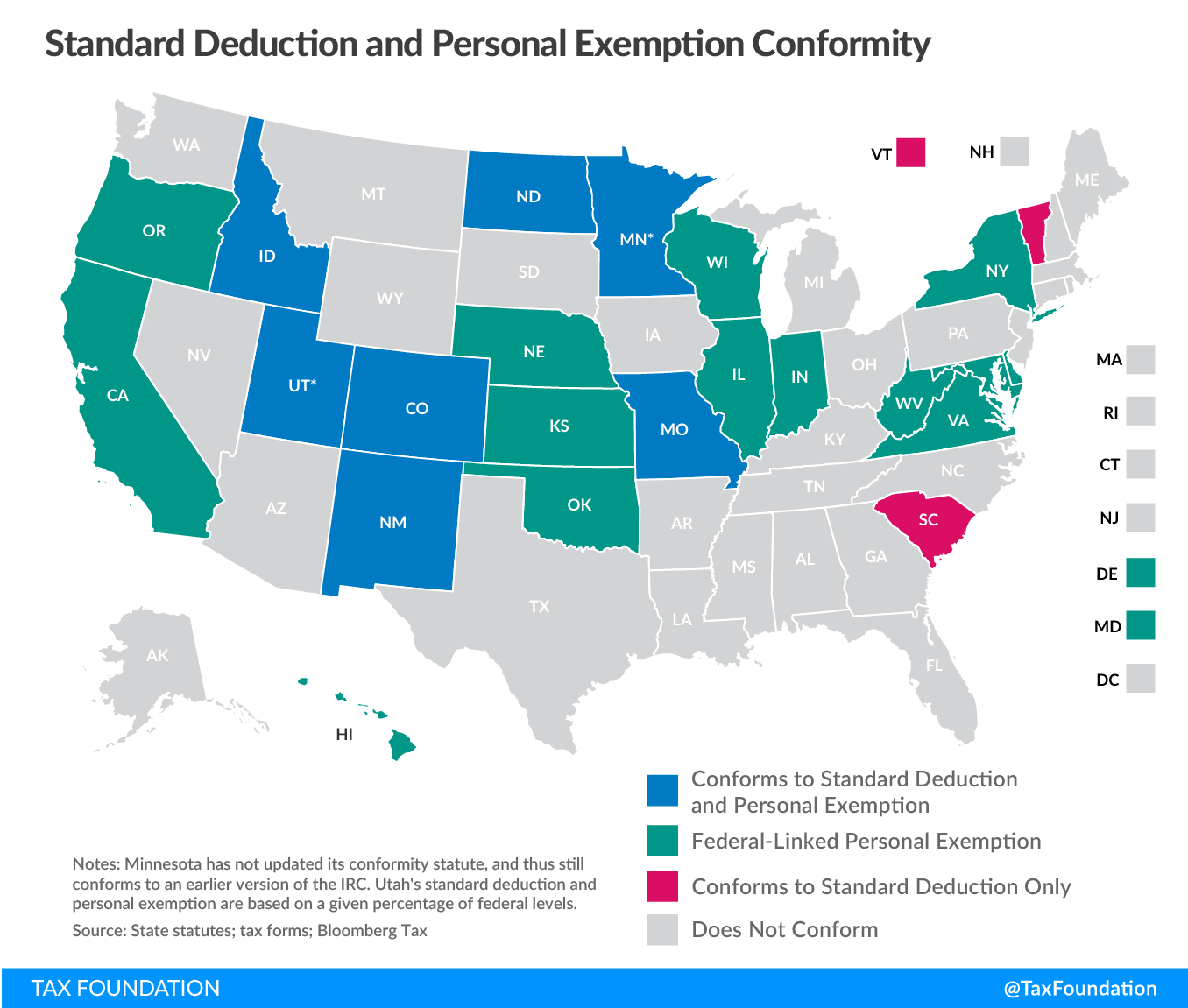

Federal tax reform will also affect state taxes in more subtle ways, even where state tax codes are unaffected. With a far more generous standard deduction and a curtailment of some itemized deductions, far more taxpayers can be expected to take the standard deduction rather than itemizing on their federal tax return, a decision which affects the taxpayer’s ability to itemize state taxes in some jurisdictions. Before tax reform, about 30 percent of filers itemized. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that only 12 percent will do so for tax year 2018.[16]

If federal changes influence a taxpayer’s choice of filing status (i.e., from married filing jointly to married filing separately or vice versa), this too can constrain choices at the state level, since many require that taxpayers use the same filing status on their federal and state returns.

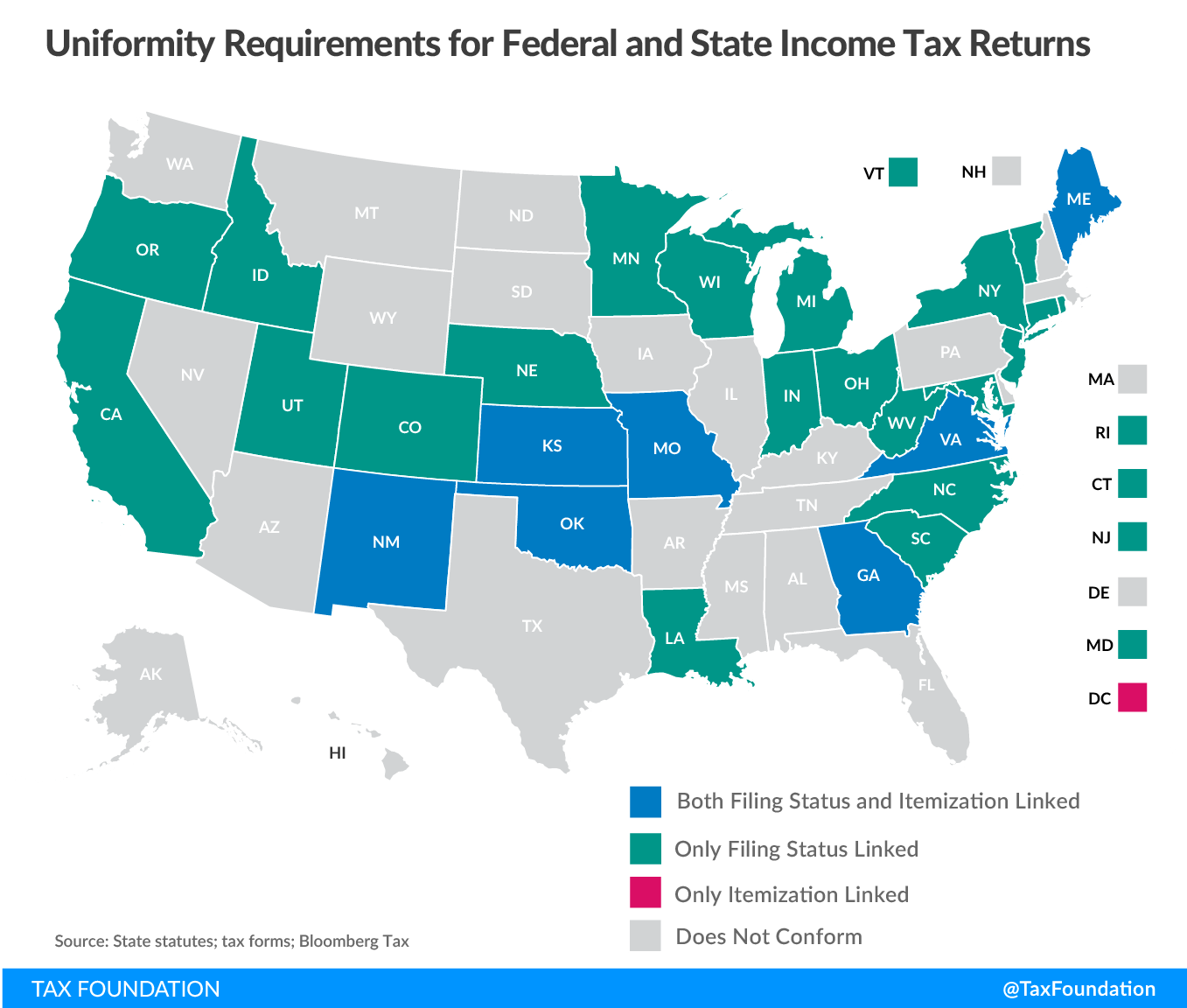

Figure 4.

In some cases, there will be filers who would have been better off itemizing at the state level but who are forced to take the standard deduction because doing so is disproportionately beneficial to them at the federal level, and they are required to follow their federal filing choice on their state return. If these filers now elect to take advantage of the higher federal standard deduction, they must take their state’s standard deduction as well, even if itemization would be more advantageous to them. (In states with exceptionally generous standard deductions, the opposite effect is possible.) In Virginia, for instance, a revenue forecast commissioned by the state estimated more than $250 million a year in additional revenue from taxpayers shifting to the state’s stingy standard deduction.[17]

Notes: Not all states offer itemized deductions. Pennsylvania offers neither standard nor itemized deductions. New Hampshire and Tennessee tax interest and dividend income only.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

With federal tax reform, small businesses have seen an expansion of the Section 179 small business expensing provision, which allows certain investments in machinery and equipment to be fully expensed in the year of purchase. This provision flows through to the states which conform with federal tax treatment.

Under the old law, small businesses could expense up to $500,000 in the year of purchase, with the benefit beginning to phase out above $2 million. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act raised the expensing cap to $1 million and begins the phaseout at $2.5 million. Thirty-one states adopt federal Section 179 expensing allowances and investment limits, while two states conform to a stated percentage of federal levels and eleven states offer small business expensing regimes with their own expensing limits. (Of these, Pennsylvania uses federal levels, but for a specified prior year, independent of the state’s general conformity date.) Connecticut, which conformed to federal levels prior to the enactment of the TCJA, has implemented an 80 percent add-back to reduce the value of Section 179 expensing in the state.[18]

Section 179 applies to businesses on the basis of size, not entity formation, and is thus available to small C corporations as well as pass-through businesses. Because of its phaseout levels, however, it is overwhelmingly utilized by pass-through businesses against individual income tax liability. The full expensing provisions of the new federal law, discussed later, should render Section 179 expensing almost exclusive to pass-through businesses, hence its inclusion in the individual income tax section of this paper. However, because it is not legally limited to such entities, the deduction is available in states which forgo individual but not corporate income taxes.

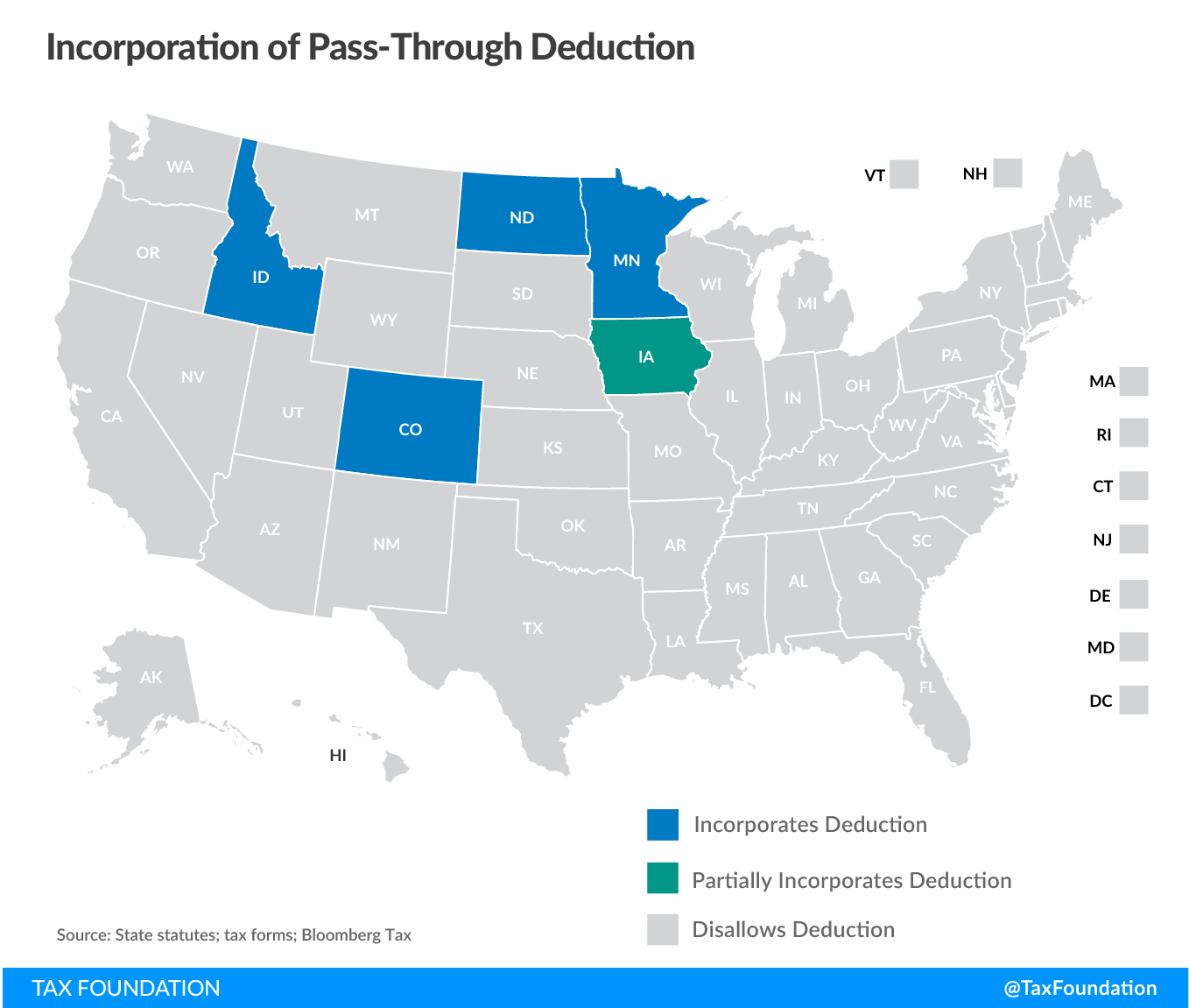

A new federal provision, the deduction for qualified pass-through business A pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income (QBI), affects a smaller number of states. The new provision provides a 20 percent deduction against qualified pass-through business income for those with incomes below $315,000 (if filing jointly). For those above that threshold, the deduction is limited to the greater of (a) 50 percent of wage income or (b) 25 percent of wage income plus 2.5 percent of the cost of tangible depreciable property. Above the threshold, moreover, many professional services firms are excluded.[19]

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the deduction will cost the federal government $414.5 billion over the ten-year budget window, so states which conform to the provision could face a meaningful revenue loss.[20] Consequently, it has understandably emerged as a point of consternation, and several states took steps to decouple from the provision in 2018.

A state’s individual income starting point determines whether pass-through businesses will receive the benefit of the deduction at the state as well as the federal level. Crucially, it is structured as a deduction against taxable income, not adjusted gross income. As such, it originally stood to be incorporated into the tax codes of Colorado, Idaho, Minnesota, North Dakota, Oregon, South Carolina, and Vermont, all of which used federal taxable income when the new federal law was enacted. Uncertainty also existed in Montana due to its inclusion, by statute, of a large swatch of federal deductions. Ultimately, however, Montana adopted a rule expressly disallowing the deduction,[21] while Oregon and South Carolina decoupled from it.[22] Vermont went a step farther, adopting federal AGI as its new income tax starting point, thus avoiding the pass-through deduction.[23] Conversely, Iowa selectively conformed to the deduction at a partial rate as part of a broader tax package adopted in 2018.[24]

Figure 5.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

This leaves Colorado, Idaho, Iowa (partial), Minnesota, and North Dakota as the states still tied to the pass-through deduction, though Minnesota has yet to update its conformity date to capture the change. States wishing to avoid the pass-through deduction can disallow the deduction expressly by adding back the amount of the deduction into state taxable income, or indirectly by adopting federal AGI as their income starting point.

Notes: Section 179 primarily benefits pass-through businesses but can be claimed by C corporations as well. Pennsylvania has fixed-date Section 179 conformity.

Sources: State statutes; state revenue departments; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

Federal tax reform ushered in a major overhaul of corporate taxation. The new tax law brings the corporate income tax A corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate in line with the rest of the developed world, overhauls the international taxation regime, changes the tax treatment of capital investment, and modifies or eliminates several targeted tax preferences.

The law modernizes the U.S. tax code by shifting from a worldwide to a territorial tax regime, which is in line with most developed nations. Under a worldwide system, all income, no matter where earned, is subject to domestic taxation, but with credits for taxes paid to other countries. Under a territorial system, a company is only taxed on domestic economic activity. The new U.S. territorial tax system includes a base erosion anti-abuse tax and rules about effectively connected income, designed to counter international tax sheltering or other tax avoidance techniques. The inclusion of Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) in the base is of particular significance at the state level.

The new law also allows the full expensing Full expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of short-lived capital assets—essentially, investment in machinery and equipment—for five years, after which the provision phases out. The corporate income tax is imposed on net income (after expenses), but traditionally, investment costs must be amortized over many years, following asset depreciation schedules. This creates a bias against investment, and this disparate treatment has long been in the crosshairs of reformers. The new law does not eliminate depreciation Depreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. schedules altogether but allows purchases of machinery and equipment to be expensed immediately. This new cost recovery system builds on the prior “bonus depreciation” regime, under which 50 percent of the cost of new machinery and equipment could be expensed in the first year.

At 21 percent, the new corporate income tax rate is now in line with averages for developed nations, while certain deductions, most notably the Section 199 domestic production activities deduction, have been modified or (as in the case of Section 199) repealed. Net operating losses (NOLs) may now be carried forward indefinitely, but carrybacks are disallowed and the amount of losses that can be taken is capped at 80 percent of tax liability in a given year.

While corporate income taxes generally constitute a modest share of state revenue, limiting the impact these changes will have on state coffers, they nonetheless flow through to states in ways worth exploring.

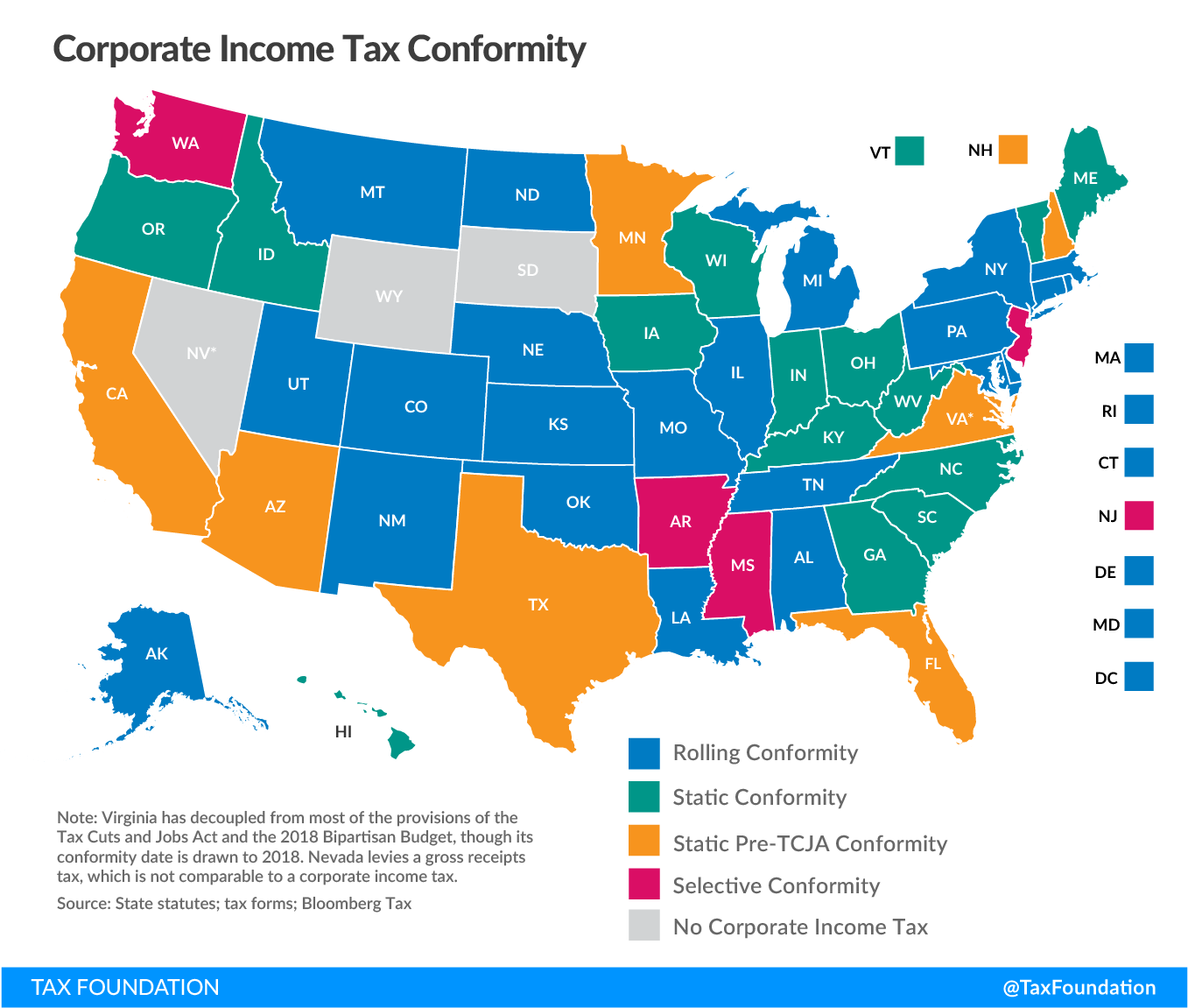

Forty-five states and the District of Columbia impose corporate income taxes. Of these, sixteen begin their calculations with federal taxable income, while twenty-one adopt federal taxable income before net operating losses and special deductions as their starting point. (Both options represent lines on the federal corporate income tax return.) Alabama, North Carolina, and Vermont use federal taxable income before NOLs but not special deductions.

Louisiana and the District of Columbia begin with federal gross receipts and sales before making a range of adjustments to approach a net figure, while Arkansas and Mississippi implement state-specific calculations. Four states (Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington) use gross receipts taxes in lieu of corporate income taxes (though Texas uses federal gross receipts and sales as a starting point in its gross receipts tax A gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding. calculations), while South Dakota and Wyoming forgo both corporate income and gross receipts taxes.

Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia adopt rolling conformity, implementing changes to the Internal Revenue Code as they are made. Of these, however, Michigan allows taxpayers the choice of rolling conformity or the IRC as it existed on January 1, 2012, while Maryland temporarily suspended conformity for TCJA provisions with a revenue impact greater than $5 million. Maryland will have to revisit that decision for 2019, as the suspension only lasted one year.

Twenty-one states use static conformity, and they are more likely to be a couple of years behind on corporate than individual income tax conformity. Arkansas and Mississippi use their own definitions and therefore do not conform. New Jersey also fails to conform, but stipulates that state taxable income is equivalent to federal taxable income before net operations losses and special deductions.

Fifteen states updated their fixed conformity date in 2018, leaving only six states (Arizona, California, Florida, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Virginia) which still use a pre-TCJA version of the Internal Revenue Code for corporate tax purposes. (Texas uses the 2007 definitions for its gross receipts tax.) However, while Virginia updated its conformity date, it expressly excluded all federal tax law changes for 2018 and subsequent years, and thus fails to conform to most of the provisions of the new federal law.

Figure 6.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

State tax codes and revenues are influenced by a range of corporate tax changes, including the loss or reform of certain business deductions, modification of the treatment of net operating losses, the full expensing of machinery and equipment, the limitation of the net interest deduction, and the inclusion of international income. States which adopt full expensing and decouple from GILTI could see reduced corporate revenue, though the revenue-positive changes to individual income taxes are far more significant for states’ revenue outlooks. Conversely, states which decouple from full expensing but adopt net interest deduction limitations, net operating loss revisions, and potentially even GILTI taxation, could impose large and uncompetitive new burdens on businesses absent reform.

A state’s choice of corporate income starting point is significant for treatment of net operating losses—even though most states adopt their own set of modifications—as well as the potential inclusion of international income.

(a) Virginia has decoupled from most of the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the 2018 Bipartisan Budget.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

Net operating losses (NOLs) occur when a company’s tax-deductible expenses exceed revenues. Corporate income taxes are intended to fall on net income, but business cycles do not fit neatly into tax years. Absent net operating loss provisions, a corporation which posted a profit in years one and three but took significant losses in year two would not be taxed on its net income over those three years, but rather on the profits of years one and three, without regard to the losses in year two.

To address this problem, the federal tax code permits net operating losses to be carried into other tax years. Under prior law, they could be carried forward up to twenty years and backward up to two years. The new tax law eliminates NOL carrybacks but allows indefinite carryforwards. The amount of losses that can be taken in a given year, however, may not exceed 80 percent of tax liability, ensuring that NOL carryforwards cannot eliminate a company’s tax liability.

Few states conform fully to federal net operating loss provisions. More frequently, states “shadow” federal NOL treatment in a variety of ways, bringing portions of the federal code into state definitions but diverging in various respects.

Sixteen states use a net taxable income starting point, which includes net operating losses. Many of these, however, require that NOLs be added back to taxable income, even if they subsequently offer their own NOL deduction. Separately, many states which use a starting point prior to the NOL deduction subsequently provide their own subtraction from income, representing a state NOL deduction.

Whether states begin their corporate income tax calculations before or after the NOL deduction says less about whether they offer a deduction than about how that deduction conforms to federal provisions. Of significance in the wake of federal tax reform is not the intricacies of each state’s NOL regime, but whether states conform to the number of years that NOLs are permitted to be carried forward and backward. A few states conform on years a loss can be carried forward, but disallow carryback losses. Since federal law no longer allows carrybacks, a state is listed as conforming on how long NOLs can be carried so long as it conforms with carryforward provisions, even if statutes require an add-back for carrybacks.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

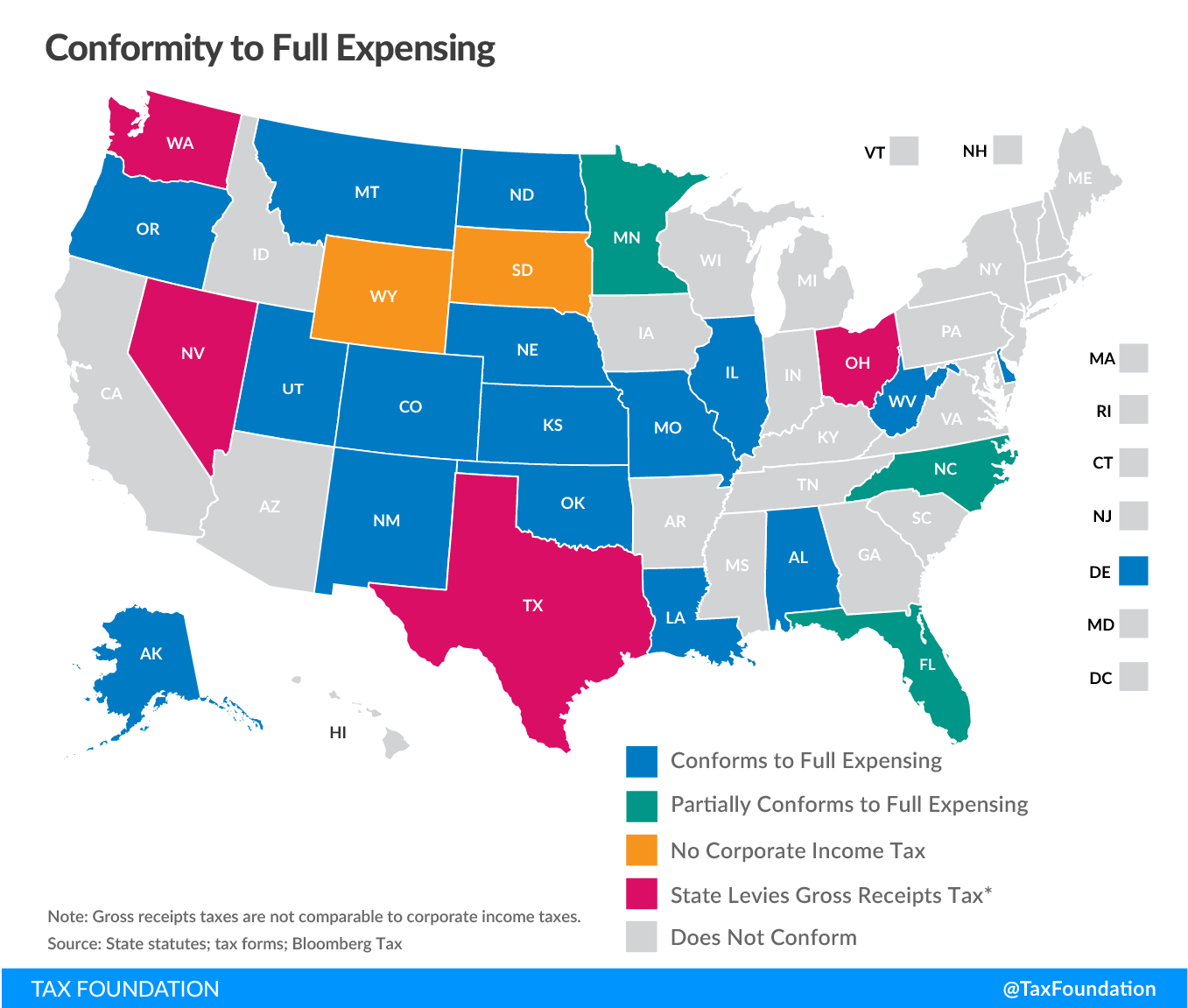

The new federal law’s more favorable treatment of capital investment, described previously, flows through to some states. Federal law now allows purchases of short-lived capital assets (machinery and equipment) to be expensed immediately, rather than depreciated over many years. This replaces the prior bonus depreciation regime, which offered accelerated (but not immediate) depreciation. Sixteen states conform to IRC § 168(k) and thus follow the federal government in offering full expensing of machinery and equipment purchases. Another three states (Florida, Minnesota, and North Carolina) conform with partial addbacks, allowing a given percentage (for instance, 20 percent in Minnesota) of the bonus depreciation offered at the federal level.

Although full expensing reduces state revenue, it is also highly pro-growth, and states would do well to conform to this provision. Accepting this cost should be made easier in that most states can expect a broader overall tax base due to federal tax reform. Within this context, it makes sense to incorporate provisions which drive economic expansion.

Figure 7.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Federal law now restricts the deduction of business interest, limiting the deduction to 30 percent of modified income, with the ability to carry the remainder forward to future tax years. For the first four years, the definition of modified income is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA); afterwards, a more restrictive standard of gross income less depreciation or amortization (EBIT) goes into effect.[25]

These changes mean that a greater share of interest costs will be taxable, increasing revenue. Of particular note, additional capital investment can limit interest deductibility under EBTI. Given this change, which increases the cost of investment, states would do well to ensure that they also conform to the new full expensing provision, which was intended as a counterbalance. Five states—Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and Wisconsin—legislatively decoupled from the net interest limitation in 2018.

The TCJA also repeals the Section 199 domestic production activities deduction, which provided a deduction worth 9 percent of domestic production gross receipts (or taxable income, if less), meant to advantage domestic manufacturing. Many states, either due to their corporate income starting point or an express linkage, conformed to the Section 199 deduction. Its elimination, therefore, represents a broadening of the base for states which had previously offered the preference.

(a) Despite static conformity, Florida automatically conforms to changes affecting the definition of taxable income, including the elimination of Section 199 deductions

(b) Virginia has decoupled from most of the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the 2018 Bipartisan Budget.

Sources: State statutes; tax forms; Bloomberg Tax

At the federal level, the TCJA represented a significant retreat from the taxation of international income, but due to the way states tend to conform to the new provisions, the opposite effect is playing out in many states. Prior to the new tax law, the federal corporate income taxes applied to the entire worldwide income of a firm, with credits for foreign taxes paid. Now the U.S. operates under a mostly territorial system, with a few guardrails to curb international tax avoidance techniques like profit shifting and the parking of intellectual property in low-tax countries.

The adoption of a more internationally competitive corporate income tax rate and the shift to a territorial tax system A territorial tax system for corporations, as opposed to a worldwide tax system, excludes profits multinational companies earn in foreign countries from their domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. will have significant impacts on business decision-making. The immediate state impact of changes to the structure of international taxation, however, depends on how states conform on provisions related to the new inclusion for Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), the repatriation of foreign income, and several other provisions.

Prior to the enactment of federal tax reform, American corporations had about $2.6 trillion in overseas reinvested earnings.[26] Under the old “worldwide” system of taxation, U.S. corporations paid the difference between the U.S. statutory corporate income tax rate of 35 percent and the statutory rate in the other nation where the income was earned. However, that liability was deferred so long as the income was reinvested. As part of the transition to a territorial tax code, these deferred earnings were “deemed” to have been repatriated, meaning they are immediately taxable by the federal government at rates of 15.5 percent on liquid assets and 8.0 percent on illiquid assets. This repatriated income is included in what is known as Subpart F income.

Whether states include Subpart F income in their tax base and whether they conform to the new deduction for federal dividends received helps dictates whether they receive additional revenue from income “deemed” repatriated. Since the income was deemed to be repatriated as of the end of calendar year 2017, states which do not tax Subpart F income are unable to revise their treatment of repatriated income to take advantage of this change.

Deemed repatriation is a one-time event, though its impact extends past 2018 since companies have the option to spread payments over eight years. Given the time-limited nature of deemed repatriation, however, states should avoid appropriating the money for recurring expenses or using it to pay down permanent tax relief. Rather than incorporating it into the budget baseline, states might consider depositing any repatriation windfall in pension funds or rainy-day funds, or using it for one-time expenditures.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

When a foreign subsidiary of a domestic corporation pays a dividend to its U.S. parent, the federal government provides a deduction for the foreign-source portion of dividends received,[27] consistent with the principles of a territorial tax system. States can theoretically diverge from federal treatment in two different ways: in their definitions of dividends received and whether they provide the 100 percent deduction of foreign dividends.

Because of the way state tax codes are drawn, some states technically incorporate the dividends received deduction even though they do not include foreign dividend income in the first place. Excluding dividends received from the initial definition of income is more robust, as there are eligibility limitations on the availability of the corresponding deduction. Some states include a portion of foreign dividends in the tax base, or only the dividends from certain types of firms.

Eighteen states and the District of Columbia exclude dividends received from definitions of income altogether, while twenty include (or partially include) the income but provide a corresponding deduction. Seven states include, or partially include, foreign dividends in their tax base and fail to conform to the foreign dividends received deduction (DRD). Cutting through this complexity, fifteen states stand to obtain new revenue from the transition tax on repatriated income due to their Subpart F and foreign dividend rules.

Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax; Deloitte

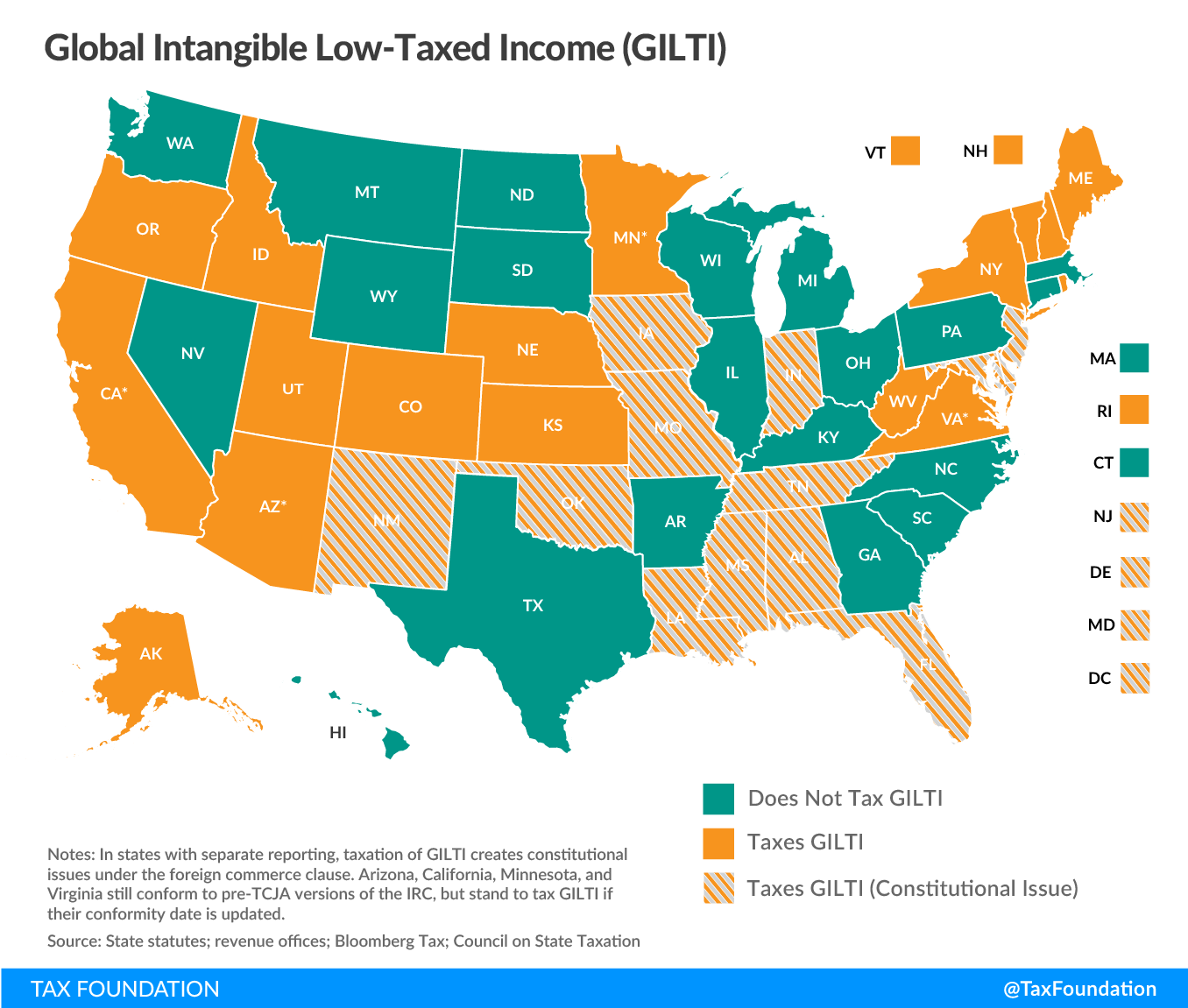

Two TCJA guardrails, the inclusion of Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) in the base and the imposition of a Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), can return some international income to the federal tax base, and the GILTI inclusion in particular has profound implications for state taxation. At the federal level, the GILTI inclusion functions in tandem with other provisions which tend to be lacking in state codes. Consequently, not only does conformity to GILTI involve state taxation of international income, but it tends to yield a far more aggressive international tax regime than the one implemented by the federal government.

Although the name implies that GILTI applies specifically to returns on intangible property (like patents and trademarks) parked in low-tax countries, that effect is only approximated by the interaction of multiple IRC provisions. Although GILTI calculations can be highly complex, in simplified form, they tax what are deemed the supernormal returns of foreign subsidiaries, less a deduction, less a calculated partial credit for foreign taxes paid.

The inclusion (under IRC § 951A) is for what are considered “supernormal returns,” defined as income above 10 percent of qualified business asset investment less interest expenses, the idea being that this is a reasonable rate of return on capital investment, and that higher returns are likely to be royalty income or other income associated with profit-shifting. (This is not, it bears noting, always the case.) A GILTI deduction is then offered at IRC § 250, currently worth 50 percent (declining to 37.5 percent after 2025), bringing the U.S. federal tax rate on this income from 21 to 10.5 percent (13.125 percent after 2025). Finally, business taxpayers may claim a credit equal to 80 percent of their foreign taxes paid on that income. These foreign tax credits are also subject to an overall limitation equal to U.S. tax liability times foreign profits divided by worldwide profits. In general, however, the higher the foreign tax liability, the lower the residual U.S. liability.

Many states conform to the corporate code before credits or deductions, thus bringing in GILTI under § 951A, but without the 50 percent deduction or the credits for foreign taxes paid. Consequently, state taxation of GILTI is far more aggressive than federal taxation, and in particular, lacks any pretense of only applying to low-taxed foreign income. In some cases, state effective rates could rival the federal rate on GILTI.[28] Any such taxation represents a substantial departure from states’ more typical waters-edge tax systems, which generally avoid taxing international income, and raises serious constitutional questions. Some states are exploring “factor relief” to reduce these costs. However, taxing GILTI—even with, but especially without, the § 250 deduction and factor relief—is highly uncompetitive, and states should avoid it altogether.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Separate reporting states have a particularly compelling reason to decouple, as the U.S. Constitution forbids discriminatory taxation of foreign economic activity. If a state does not include U.S.-based subsidiaries in a consolidated group for taxation, it cannot include international subsidiaries (controlled foreign corporations) within the filing group for tax purposes. Doing so would violate the foreign commerce clause, granting Congress the sole authority to regulate commerce with foreign nations and other states, by treating international income less favorably than domestic income.

States which use separate (rather than combined) reporting and nevertheless seek to tax GILTI face a serious constitutional challenge, particularly under the precedent of Kraft v. Iowa Department of Revenue (1992), a U.S. Supreme Court case striking down a business tax that allowed a deduction for dividends received for domestic, but not foreign, subsidiaries.[29] These states should take particular pains to avoid taxing GILTI.

Importantly, although it resides in the same part of the federal tax code and is treated similarly for federal tax purposes, GILTI is not Subpart F income, and a state’s inclusion or exclusion of Subpart F income in its tax base has no bearing on its taxation of GILTI.[30] A state’s treatment of the foreign dividends received deduction (discussed previously) can, however, be relevant, as some states have eliminated GILTI liability by allowing it to be deducted as foreign dividend income.

Figure 8.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Generally speaking, states include GILTI in their base unless they use state-specific income starting points or expressly decouple from it. States which begin with federal taxable income before special deductions (line 28 of the corporate income tax form) generally forgo the corresponding 50 percent deduction, while states which begin with federal taxable income after special deductions (line 30) generally include it, though here too, states may adjust their conformity to this specific provision legislatively. Furthermore, some states have made administrative determinations that GILTI is not part of taxable income, or that it can be fully (or very nearly so) deducted as a foreign dividend.

Several states acted on GILTI taxation in 2018. Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, North Dakota, and Pennsylvania determined that GILTI could be fully offset by the dividends received deduction. Georgia, Hawaii, and South Carolina legislatively decoupled from the inclusion of GILTI in the tax base. And New Jersey adopted conformity with the partially offsetting § 250 deduction.

Due to complexity, the table below includes statutory elements—like whether a state’s code begins with a GILTI inclusion—as well as administrative determinations to allow a 100 percent dividend deduction for GILTI, and adds a summary column for ease of understanding.

(a) Conforms to a prior year and does not yet include GILTI.

(b) California separately taxes controlled foreign corporations and may not be able to tax GILTI in addition.

(c) Maine provides a 50 percent subtraction modification for GILTI but adds back the federal deduction.

Sources: State statutes; revenue offices; Bloomberg Tax; Council on State Taxation

Whereas GILTI involves the taxation of the foreign intangible income of domestic corporations, the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) deduction provides a benefit to companies that generate export-related income on U.S.-based intangible property. Many have termed this the carrot-and-stick approach to international taxation, where FDII is the carrot and GILTI the stick.[31]

Like the deduction against GILTI, the FDII deduction is in § 250, though the two are separate and should not be confused. States which conform to the GILTI deduction in that IRC section typically offer the FDII deduction as well, but a few have legislated the matter separately.

Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax

In 2018, six states—Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Missouri, Utah, and Vermont—adopted rate cuts or other reforms designed, at least in part, as a response to the expectation of increased revenue due to federal tax reform. Their distinct approaches pattern a range of options available to other states.

In Georgia, lawmakers reduced the top individual and corporate income tax rates from 6 to 5.75 percent in 2019 while doubling the standard deduction. Further rate reductions, to 5.5 percent on both taxes, are anticipated for 2020, but will require a joint resolution affirming the legislature’s continued assent.[32]

Idaho implemented a 0.475 percentage point cut in the corporate income tax rate and across all marginal individual income tax brackets A tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. and introduced a new child tax credit to offset additional revenue associated with federal tax conformity. The child tax credit was created to account for the impact of the loss of the personal exemption for larger families.[33]

A broader tax reform package advanced in Iowa, helped along by projected conformity revenue. Over the course of several years, Iowa’s top individual income tax rate will fall from 8.98 to 6.5 percent, while the corporate income tax rate will decline from 9.8 percent. The tax package includes the repeal of the alternative minimum tax as well as the phaseout of Iowa’s unusual deduction for federal taxes paid.[34]

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

In Missouri, the top individual income tax rate was cut from 5.9 to 5.4 percent, partially offset by a phaseout of high earners’ federal deductibility, and a corporate rate cut is set to follow in 2020. As in Iowa, a broader tax package was facilitated in part by federal conformity revenue, particularly since the state conformed to the repeal of the personal exemption.[35]

Utah shaved its individual and corporate income tax rates from 5.0 to 4.95 percent and approved an expansion of the child tax credit to offset additional revenues expected from tax conformity.[36]

And Vermont eliminated its top individual income tax bracket and reduced the remaining marginal rates by 0.2 percent across the board.[37]

In several cases, federal tax reform was the primary impetus for state reform. In others, additional revenue from tax conformity served as an important pay-for in a broader reform plan. States which have yet to update their conformity dates may look to them for inspiration, but even those that have already conformed should consider their options, particularly if tax collections have risen markedly due to tax conformity. There is a unique window of opportunity for reform.

Some states responded to federal tax reform by overhauling their own tax codes, or at least acting to avoid unlegislated tax increases. Yet, more than a year after tax reform, many states are still deferring important decisions. If policymakers wish to use base broadening to pay down rate cuts or structural reforms, the clock is ticking: what is still conformity revenue in 2019 will start to be viewed as part of the baseline very soon. Meanwhile, uncertainty persists, especially in the realm of international taxation, with a great deal riding on those decisions.

Most states have experienced additional revenue due to base-broadening provisions of federal tax reform. Although this additional revenue does not match the windfall experienced after tax reform in 1986, when all but one state with an individual income tax conformed the subsequent year,[38] the increases are substantial for some states, particularly those which conform to the now-repealed federal personal exemption. The handful of states that faced potential revenue losses took steps in 2018 to forestall that outcome.

States facing a loss of revenue due to the pass-through deduction may wish to decouple from that provision, either by adopting federal AGI as their income starting point or by expressly adding back the new pass-through deduction. Montana, Oregon, South Carolina, and Vermont all decoupled from the provision in 2018, and this could be an option for the remaining conforming states as well.

If a state is out of compliance with federal expensing provisions, one of the most pro-growth responses to the additional revenue capacity is to conform to federal treatment of Section 168(k), full expensing of machinery and equipment, and to Section 179, small business expensing. These policies eliminate disincentives for investment and growth baked into the tax code, and thus have the highest return. If necessary, conformity could be phased in over time.

State taxation should stop at the water’s edge. The taxation of GILTI is uncompetitive, complex, and potentially much more aggressive than the regime implemented at the federal level. For many states, moreover, it is likely unconstitutional to tax GILTI without adopting broader changes to the state’s tax code. States should offer a subtraction for GILTI or allow it to be fully deducted under the state’s dividends received deduction.

In the aftermath of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, eighteen states reduced individual income tax rates, twenty-three increased the standard deduction, and twenty-two increased the personal exemption, among other changes.[39] In the wake of the TCJA, revenue changes are smaller, but states still have an opportunity to avoid an unintentional tax increase by adopting individual and corporate income tax cuts. A less desirable option would be to decouple from federal provisions responsible for the additional revenue.

As a far superior consideration, they could view federal tax reform as a golden opportunity to reform their own tax codes. After 1986, nine states (Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, and West Virginia) overhauled their individual income tax codes.[40] A smaller number of states made substantial changes to corporate income taxes. In 2018, states like Georgia, Iowa, Missouri, Utah, and Vermont cut rates and implemented other reforms in anticipation of a TCJA windfall. States which have yet to update their conformity statutes should strongly consider doing likewise, and even those that have already conformed would be well advised to explore options to use some or all of the new revenue to improve tax competitiveness, avoiding an unlegislated tax increase.

Lower federal corporate income tax rates will increase the scope of viable investments, and states are necessarily in competition for that investment. Reduced federal tax burdens also increase the relative importance of state taxation. States which act decisively have an opportunity to position themselves favorably, and additional revenue from base broadening grants them some room to maneuver.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Neutrality is an essential goal of tax reform. It represents the understanding that the goal of taxation is to raise revenue, not to engineer particular economic outcomes. Unfortunately, most tax systems fall far short of this goal, picking winners and losers through the tax code by subsidizing certain activities and industry sectors while penalizing others. By favoring some choices over others, tax codes distort economic decision-making to the detriment of economic expansion. Among other things, tax reform involves leveling the playing field.

Doing so is popular with those who lacked access to targeted incentives and other preferences, but unsurprisingly less popular with those who worked the old system effectively. States are sometimes wary of tax reform because officials fear leaving any business or individual worse off—even if their prior liability was solely the result of undesirable tax preferences. An infusion of additional state revenue, like that associated with federal base broadening, offers states a cushion. It allows them to make their tax codes more neutral and pro-growth while ensuring that a broader percentage of taxpayers are held harmless or made better off due to reform. Enactment of the TCJA provides a golden opportunity for states ready to act on tax reform.

At the same time, states should be careful to distinguish recurring revenue from one-time windfalls. Deemed repatriation is a one-time event, even though some payments may continue to be made for several more years, and any windfall experienced due to international transition rules should not be added to a state’s budget baseline, allocated to recurring expenses, or returned to taxpayers in the form of permanent rate reductions. To the extent that states received or anticipate further revenue from repatriation, they would do well to deposit the windfall into pension or rainy day funds, or to appropriate it for one-time projects.

The federal tax code is imperfect. That was true before federal tax reform and it remains true today. Nevertheless, there are important advantages to conforming to the current version of the Internal Revenue Code. Doing so offers greater certainty and reduces both administrative and compliance costs. It reduces the likelihood that provisions will work at cross-purposes. It cuts down on tax planning.

The argument is not that the federal tax code is, in all particulars, better than what the states could come up with; it is not. Rather, federal conformity is the lodestar because, whatever the flaws of the IRC, it is better than fifty radically different tax codes. States should move in the direction of greater conformity, not less, in the wake of federal tax reform.

Tax reform did not end with the implementation of H.R. 1 in December 2017. It merely shifted from Washington, D.C. to state capitals. Similarly, state responses to federal tax reform need not be confined to 2018. What was true last year remains true today: states should avoid the temptation to impose a stealth tax increase and instead view these changes as an opportunity to make their tax codes more competitive. They should take particular care to address unresolved issues in international taxation to provide certainty and avoid unintentionally punitive corporate taxation.

At the federal level, tax reform has proven a generational event. At the state level, it need not be—but there is no time like the present to ensure that state tax codes are oriented toward economic growth.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Errata: An earlier version of this paper mistakenly retained outdated information about estate tax conformity. Currently, no states conform to the federal exemption threshold. Table 5 has also been updated to reflect that New York and North Carolina now allow taxpayers to itemize for state tax purposes even if they take the federal standard deduction.

[1] Kirk J. Stark, “The Federal Role in State Tax Reform,” Virginia Tax Review 30 (2010), 423, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1718606.

[2] Ruth Mason, “Delegating Up: State Conformity with the Federal Tax Base,” Duke Law Journal 62, no. 7 (April 2013), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3382&context=dlj.

[3] Harley T. Duncan, “Relationships Between Federal and State Income Taxes,” Federation of Tax Administrators, April 2005, 4-5, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/taxreformpanel/meetings/pdf/incometax_04182005.pdf.

[4] An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018 [hereinafter Tax Cuts and Jobs Act], H.R. 1, 115th Cong. (2017).

[5] The $10,000 cap on the state and local tax deduction only has a limited effect on state tax regimes, to the extent that some states allow the portion of the deduction associated with property and other local taxes (while disallowing the state tax share, which would be recursive), but may also have a modest effect on future revenue capacity, as it limits the ability of states and localities to export a portion of their tax burden to taxpayers nationwide. Expanding the allowable utilization of 529 education savings plans, moreover, may result in an increase in deposits, which could affect states with 529 contribution deductions.

[6] U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 Annual Surveys of State and Local Government Finances, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/gov-finances.html.

[7] See Tax Foundation, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/, finding increases in after-tax income After-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. for all income groups; Amir El-Sibaie, “Who Gets a Tax Cut Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act?” Tax Foundation, Dec. 19, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-taxpayer-impacts/, calculating liability for sample taxpayers; and Tax Policy Center, “Distributional Analysis of the Conference Agreement for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/distributional-analysis-conference-agreement-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/full, finding that 80.4 percent of taxpayers receive a tax cut and only 4.8 percent experience a tax increase in 2018.

[8] Idaho and Oregon are often omitted from such lists, as certain additions to the tax code approximate AGI, and the latter is used in some calculations. Notwithstanding the starting point used on tax returns, the legal income starting point is federal taxable income, which has important implications in the wake of federal tax reform.

[9] Seven states forgo all individual income taxation, and another two (New Hampshire and Tennessee) only tax interest and dividend income.

[11] MD Code, Tax – General, § 10-108.

[12] 2018 Haw. S.B. 2821; 2018 Iowa S.F. 2417; and 2018 Me. S.P. 612.

[13] For joint filers, the phaseout begins at $400,000 of household income, up from $111,000.

[14] Tax Credits for Workers and Their Families, “State Tax Credits,” http://www.taxcreditsforworkersandfamilies.org/state-tax-credits/, 2016; state statutes.

[15] 2018 Idaho H. 463.

[16] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 through 2026,” JCX-32R-18, Apr. 24, 2018, 6, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5093.

[17] Virginia Department of Taxation, “Estimated Impact of the TCJA,” Nov. 19, 2018, http://leg5.state.va.us/User_db/frmView.aspx?ViewId=5343&s=23.

[19] The benefit phases out between $315,000 and $415,000 for those ineligible above the threshold.

[20] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The ‘Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,’” JCX-67-17, Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053.

[21] Administrative Rules of Montana 42.15.527.

[22] 2018 Or. S.B. 1528; 2018 S.C. H.5431.

[24] 2018 Iowa S.F. 2417.

[25] Stephen Entin, “Conference Report Limits on Interest Deductions,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 17, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/conference-report-limits-interest-deductions/.

[26] Erica York, “Evaluating the Changed Incentives for Repatriating Foreign Earnings,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-repatriation/.

[27] The dividends received deduction is subject to a 10 percent ownership requirement and other rules.

[29] Kraft Gen. Foods, Inc. v. Iowa Dept. of Revenue and Finance, 505 U.S. 71 (1992).

[30] Linda Pfatteicher, Jeremy Cape, Mitch Thompson, and Matthew Cutts, “GILTI and FDII: Encouraging U.S. Ownership of Intangibles and Protecting the U.S. Tax Base,” Bloomberg Tax, Feb. 27, 2018, https://www.bna.com/gilti-fdii-encouraging-n57982089387/.

[33] 2018 Idaho H. 463.

[34] 2018 Iowa S.F. 2417.

[35] 2018 Mo. H.B. 2540.

[36] 2018 Utah H.B. 293.

[37] 2018 Vt. H.16, Spec. Sess.